Lecture

6a:

Visionaries: Inter-Spirituality

Adam Blatner

(This is the 6th and

last

in a 6-lecture series for Senior University Georgetown, October

31,

2011)The first lecture, introduced the idea of visionary and the different types, considering the paradigm shifts happening today.

|

| Clokwise

from top: Sikh, Christian, Hindu (Om), Buddhist (Eightfold Path),

Islam, Shinto, Judaiems, Baha'i , Confucianism (at bottom), Taoism,

Unitarianism, Native American, Wicca, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, New

Thought... |

The third lecture addressed visionaries in education, which is one extension of psychology.

The fourth lecture extended these last two into the field of education

The fifth lecture considered the idea of consciousness evolution. (See the lecture given on that subject in 2009).

In this last lecture we consider interspirituality . (This also speaks to the lecture series given for the Senior University in the Spring of 2009.);

On another related webpage, I offer a summary.

- - - - - - - - - - -

This lecture will be about visionaries in the general area of religion, and more specifically, "inter-spirituality," which is a step beyond interfaith dialogue. Interspirituality seeks to appreciate the underlying themes among all the religions.

In the first third of the 20th century, the idea of tolerance was just beginning. On the whole, many and perhaps most people had no questions that not only was their brand of religion, sometimes even their denomination or sect, not just superior to others, but solely righteous, with all the others being lost if not damned outright. More, other religions were seen as actively evil, sabotaging the good in culture. Anti-semites, anti-Catholics, and others were often mixed with open racism in newspaper columns and radio broadcasts. The Ku Klux Klan was most active in the late 'teens and throughout the 1920s.

The Second World War required a national effort towards unity, and Hollywood and other types of propaganda fought against prejudice. Although American culture was not ready for inter-racial tolerance, inter-religious tolerance was promoted, and many movies about soldiers portrayed stereotypes of Americans of Irish, Italian, Jewish, and mainline WASP (White, Anglo-Saxon Protestant) descent fighting side by side. By the end of the 1940s, open religious prejudice was becoming disreputable--though it took more than a generation to lessen significantly.

By the 1960s, though, interfaith dialogue and "ecumenicism" became a theme in many churches as well as internationally, with Pope John XXIII being a more active spokseman for this. More enlightened clergy might well have guest speakers from other religions, and some of the more University-affiliated seminaries often had teachers from other backgrounds run seminars. By the 1990s, though, more writers were taking it a step beyond, wondering what insights might be found in other religions, and more, what all religions expressed---what were the underlying common denominators. This is the "inter-spiritual" turn.

|

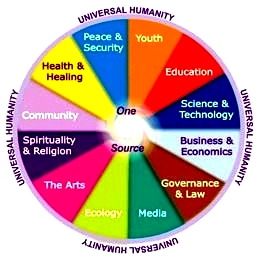

A Holistic Vision

From the first lecture, Barbara Marx Hubbard's chart suggests that many aspects of culture need to be woven together---religion and spirituality being among them. The idea is that one domain advances or co-evolves along with shifts in the basic thinking of other domains!I recently attended a conference on spirituality and pediatrics, but I was impressed with how many other domains are being considered in a more holistic approach to healing: architecture, subtle energy healing touch, neuroscience, the power of what narratives---i.e. stories---are told; and many other dimensions. You might enjoy reading some of those papers on a special website.

Definitions

Spirituality is not spiritualism. Spiritual-ism is the activity of using mediums to connect with spirits who have "passed over" (i.e. those friends or relatives who have died). It was popular starting in the mid-1800s, especially in northern New York State, and spreading outwards as a fashion for fifty years. It's still around. IN the mid-20th century spirituality and religion were not differentiated, but since the 1960s it is useful to do so, because using different words highlights different aspects of practice:.

Spirituality is the activity of deepening one's sense of connectedness to or developing one's relationship to God by many names, or purpose or source or Higher Power, and so forth. The object of the relationship may be an impersonal force or principle, yet one that is active enough to evoke a sense that one could connect to it more. Spirituality is an activity, not a state of being or an achievement. When you aren't doing spirituality you aren't doing it. It's not a status or achievement.

One can develop the skills and techniques that some folks find useful---it's a very broad range---for becoming more connected. Those who do it more intensively are what are generally called "mystics." (See my presentation on this topic on another webpage on this site.)

Religion is the social organization of spirituality. Social organizations are composed of people as well as the rules, roles, structures they develop, and all are vulnerable to the frailties of humanity. Thus, religion can become stale, rigid, fixed, eccentric, authoritarian, corrupt, and so forth, as well as all its virtures---uplifting, offering a kind of home and family, a group of comforting ideas, challenging virtues, and so forth.

Many people are religious but not spiritual. They attend church, follow many of the basic rules, don't object to the sermons, partake of the rituals, pay their dues, and so forth. It never occurs to them to make the activity part of a personal quest, something the seek to deepen or feel more intensively. Those who do---to a point---are tolerated, sometimes even admired. (There is sincere piety and a "show" of piety, but we won't go into that now.)

Some people are spiritual and religious---they exercise their process of spirituality within a religious framework that they find congenial.

Some people claim to be spiritual but not religious. That is, they remain apart from any identification or affiliation with a particular religion, denomination, or sect. It is indeed possible to be spiritual without being religious as we're talking about it. (In the old use of the word, religion, one might argue that the word included both spirituality of any type, affiliated or non-affiliated, but that's not how most folks use it. In that sense, Einstein's claim to find a religious sensibility in his ponderings of the ways of the cosmos make sense. But for our purposes, we're trying to note the difference.) Some people even have spontaneous spiritual breakthroughs without much effort, and for some this doesn't reinforce any particular dogma. For others it does support this or that element of some religion's doctrine.

Many people are neither religious nor spiritual---especially in Europe, more in some countries, less in others. Many think of themselves as agnostics, some atheists, and others won't claim any label other than "it doesn't do anything for me, so I don't bother."

The interesting feature is the spiritual---those who seek to deepen or develop---and the operative word here is "more." It's not a passive status, but an activity that one pursues with more or leas earnestness. Note that for some spirituality is not at all conventionally religious, and may partake of the philosophical teachings of both Western and Eastern thinkers. The question is whether there is a desire to go further, deeper, closer.

Mysticism

In a related paper I make the case that mysticism might be better understood as an intensification of spirituality. To use an analogy with music, there are those who just sing in the congregation. Some people want to sing with more practice and to better their skill. (This would be analogous to spirituality). Some few want to take this activity all the way, to becoming professional, doing opera, making guest appearances. Singing is far more than just getting better---it's a matter of great devotion. In the same sense, mysticism would be like becoming professionally spiritual, but generally this activity has no recognized profession. Indeed, mystics often become eccentric rather than rising in the church hierarchy, and are sometimes even accused of heresy!

Historical Precursors

There was an attitude of "my religion is better than yours" for most of history. Some groups softened this, allowing for the practice of other creeds. This was called "tolerance." In Spain in the 1300s, although Muslims were the political authority, they allowed for Jews to flourish---it was considered a "Golden Age", if they just paid a little extra tax. Over history, some groups or regimes were more oppressive than others for those not aligned with the dominant religion. |

|

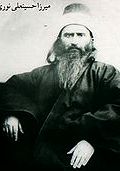

The Bahá’í religion arose in Persia in the mid-19th century.and its prophet, Baha'ullah (left) emphasized the spiritual unity of humanity. Its symbol, a nine-pointed star, here shows many of the other religious symbols included. In the last century Baha'i has become international. It has a fascinating history, was persecuted viciously for a while..

|

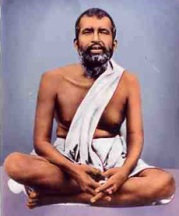

Another precursor of the idea of interspirituality is Shree (or Saint) Ramakrishna (1836 -1886) (right).. He was a simple Bengali (northeastern part of India) fellow with a deep sensitivity to spirit. Although his primary allegiance was to the Mother Kali goddess, what's fascinating about his story is that during his mature years he spent years reading and practicing other spiritual paths---Christianity, Islam, Krishna, for example---until he had some kind of vision that enlightened him on the truth of each path. He was said to have welcomed visitors by being deeply interested in their spiritual paths, asking, "Do you have a god with form or a god without form?" He didn't care---the whole enterprise of spirituality was so compelling for him.

I'll share my thinking here: I think that spiritual sensitivity is a talent in a way similar to dancing or singing or composing music is a talent. I think that one in a million are profoundly talented ---like Mozart or Beethoven---and if a culture (like India) recognizes and selects talent rather than stifling it, it's more likely to get cultivated. I think at least 50% of the very talented in all ways get it stifled in childhood, because our culture in general doesn't really value and develop all talent. Some of these kids are otherwise rather eccentric. But the whole gifted student category is gradually becoming recognized. And so some truly sensitive and bright people do fulfill their potential. So, in this sense, Ramakrishna was a Mozart of the spirit. It may well be that Yeshua ben Yusuf (aka Jesus) was also highly talented---he "got" easily, intuitively, what others could barely grasp, the way Mozart "got" music.

And even if one is not in the very top quality, there are still one in a hundred thousand in the top 5% and one in ten thousand in the top 10% in talent regarding spiritual sensitivity!

|

Swami Vivekananda (left) was one of Ramakrishna's students was more into popularizing his teacher's insights.. He came to the United states for that first International Parliament of religions (see picture below) and stayed on and gave lectures around the country. His exotic origins allowed him to spread some concepts of the more sophisticated and refined Yogic doctrines.

|

Another pioneer (shown to the right) in the early 20th century was Paramahansa Yogananda, whose book, Autobiography of a Yogi, sold well among those seeking more. His approach distilled yogic themes, exhorting readers to look within through meditation.

In general, though, the 19th century was a period of religious intolerance and colonialism (even within a country), in which minority peoples, indigenous peoples, were often persecuted and suppressed. Anti-Catholic and anti-semitic sentiments were broadcast over the radio through the 1930s. Only the challenge in the Second World War of promoting national unity generated sufficient propaganda to begin to make prejudice disreputable---though reducing prejudice requires many decades, perhaps generations, to significantly decline. Still, in the 1950s there was a growing spirit of "tolerance" in the mainstream of American culture.

In the 1960s, tolerance shifted to ecumenicism. Jokes about a minister, a rabbi, and a priest abounded. More liberal clergy read writings by clearly bright thinkers in other religions, and sometimes invited a clergyman of another religion as a guest speaker for his congregation. (Religion was still almost completely dominated by men.)

|

Starting in the late 1980s and picking up momentum, this cultural trend has moved further, into active questioning about what elements in various religions are in terms of psychology, sociology, anthroplogy, history, even genetics (i.e., evolutionary psychology). The movement had advanced to a point of considering underlying dynamics, common denominators. This trend was reflected in an international Parliament of Religion---the first one having been held in 1893:

Current Visionaries

I have been fortunate in meeting several pioneers in this field, one of whom, Brother Wayne Teasdale, died in 2004. |

|

On the far left is the interesting Father Bede Griffith, a Catholic Monk who also found in India much that was spiritually valid. Teasdale wrote a couple of books about his ideas which are worth knowing about, one being The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World’s Religions. This addresses some of the themes that circulate around the general theme of today's lecture (and this webpage.)

The idea that there are underlying themes has been discussed by me in other talks, such as a series of lectures I gave for our Senior University Georgetown in 2009 on Interfaith Spirituality in 2009. The 5th lecture in that series speaks to some of the themes in interfaith spirituality and complements this present webpage.

|

|

The Dalai Lama has also been active in this quest and this becomes clear in his latest (2010) book, Toward a True Kinship of Faiths. .His own background in the rather elaborate and strange religion of Tibetan Buddhism is in a way intriguing, because his life has taken him so far afield---and his having received a Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 added to his work. On the far right he's shown with Bro. Teasdale, perhaps in 1990s.

|

An example of this trend towards interfaith if not interspirituality has been the activities of my friend Rabbi Ted Falcon who with his friends, Imam Jamal Rahman (on the left) and *in the middle) Don McKenzie, have been witnessing nationally and internationally as a team to the viability of interfaith efforts. (I met Rabbi Falcon because he co-wrote a book with my son, David titled “Judaism for Dummies” about nine years ago.)

|

|

Another two people worth knowing about pictured at right is Matthew Fox (on the left of the two) and John Shelby Spong---two reformers working from within, affirming their dedication to Christianity as they understand it---but it's a far cry from what is being preached by a number of televangelists, literalists and fundamentalists. The point is that religion can evolve, even if you don't agree with what they're suggesting. It begins a conversation. If you are wondering about some elements of your religious belief, even if you're not a Christian, then these people's writings are mentally stimulating.

|

Some Interspiritual Trends

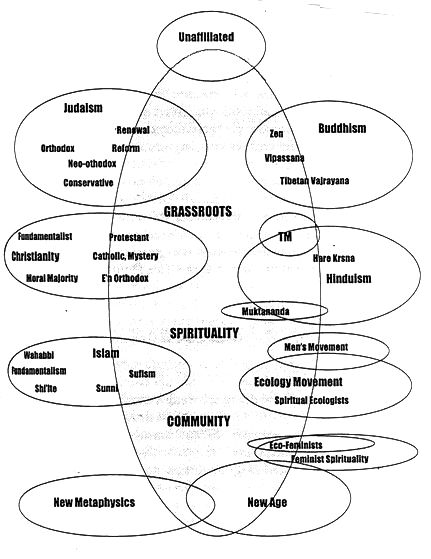

On the left is a "venn diagram" that shows how many different approaches may overlap and illustrates again how some folks are "spiritual but not religious" in that they don't remain affiliated with any particular religion. Some have chosen elements from various approaches, some have been on a "journey" through a number of different denominations or sects.28. Roger Walsh, a psychiatrist and acquaintance and pioneer of transpersonal psychology mentioned a few sessions ago, wrote a book about “essential spirituality.”

29. Here are some ideas. You don’t have to agree with this, but all I’m doing is trying to stimulate your thinking, talking with partners and friends and kids...

30. Different Paths within Spirituality

31. Yoga, different paths

The point is the recognition mentioned in the last few lectures of individuality, the growing recognition in science of the real differences between people—and the recognition that for a few centuries or more in the West, the Western religions have tended to ignore these and offered a one-size-fits-all approach. Perhaps this was necessary considering the resources they had, I don’t know; but it’s not needed today in religion nor education. Vocational guidance tests, what is your temperament, what are your interests, YOUR talents, strengths, and then from that, what are some paths that interest you? Can we get these lined up?

32. Ditto...

33. As for Yantras, some people use them—I do—to center, get grounded. You may have seen me doodling in class and often I begin with drawing this diagram.

34. A theology professor down in Austin, Corinne Ware, integrated a variation of Jung’s four temperament types and spirituality. I’ve found among my friends that it’s not a matter of arguing for my viewpoint, but rather recognizing how our differences are inevitable and deep and okay.

35. There are some words there that reflect the jargon of educated theologians, and some of those words are new to me! I had to look up “encratism” this last week–hurray for Google...

... And apophatic I only learned about a year ago... kataphatic is a bit new to me too, so theologians have their own jargon...

36 This diagram intrigued me as another mandala – you can see what I have to say about mandalas on my website... and the point is that most religions have someone who has said something in their scriptures about these topics...on the middle wheel

37. And these topics. On the outer wheel... But what’s important is that I’ve found that people who think they believe the same things have slightly different associations, meanings, feelings, stories about each of these words...often subconsciously.

38 so here’s another mandala, and with yet other spiritual symbols, such as the ancient egyptian symbol for Life, the ankh, at 9 PM

I can’t tell what that symbol is at 9:30 on the outside circle..

The ancient matriarchal pre-historic religions, as we imagine them, are at 4:30 inner ring...

And the sufi inter-spiritual path at 6:30 outside ring...

- - - - -

References

Schmidt, Leigh Eric. (2005). Restless souls: the making of American spirituality, from Emerson to Oprah. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. Some emphasis on the later transcendentalists, a goodly number doing their thing between 1830 - 1910, with some comments on events before and after. Wow, there was a whole bunch of folks who were really inter-spiritual back then!! fits right in with Bro Teasdale's message!Teasdale, Bro. Wayne. (1999).. The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World’s Religions, Forward by the Dalai Lama, Preface by Beatrice Bruleau (New World Library 1999) ISBN 157731140X

- ibid: (2002). A Monk in the World: Cultivating a Spiritual Life, Forward by Ken Wilber (New World Library 2002) ISBN 1577314379

- ibid. (2003). Bede Griffiths: An Introduction to his Interspiritual Thought, Forward by Bede Griffiths (Skylight Paths Publishing 2003) ISBN 1893361772

Walsh, Roger (1999?). Essential spirituality: the seven central practices to awaken heart and mind. New York: John Wiley.